Tracing the Past, Shaping the Future

Exhibition

5 Nov 24 — 27 Feb 25

If we care for Country, Country will care for us.

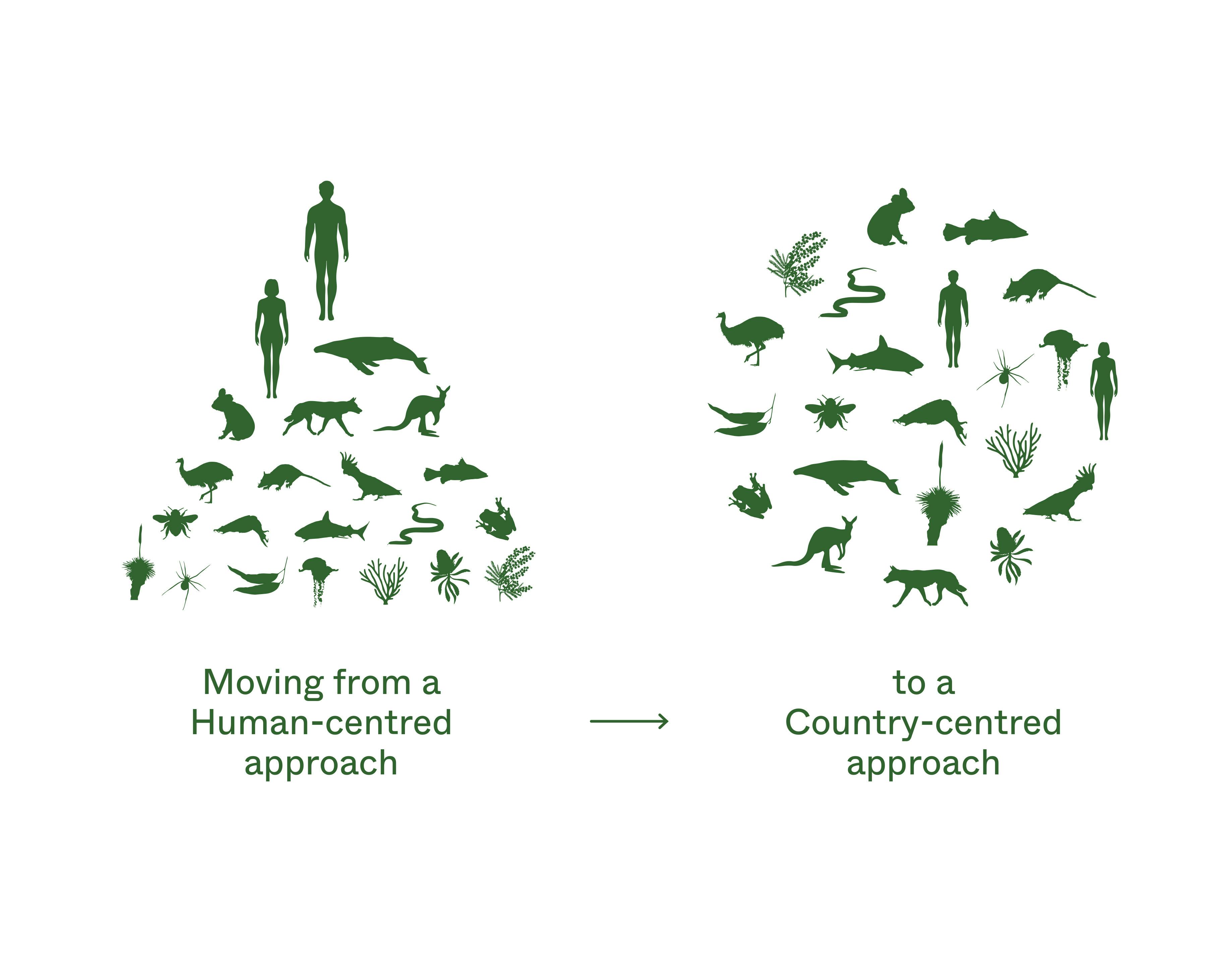

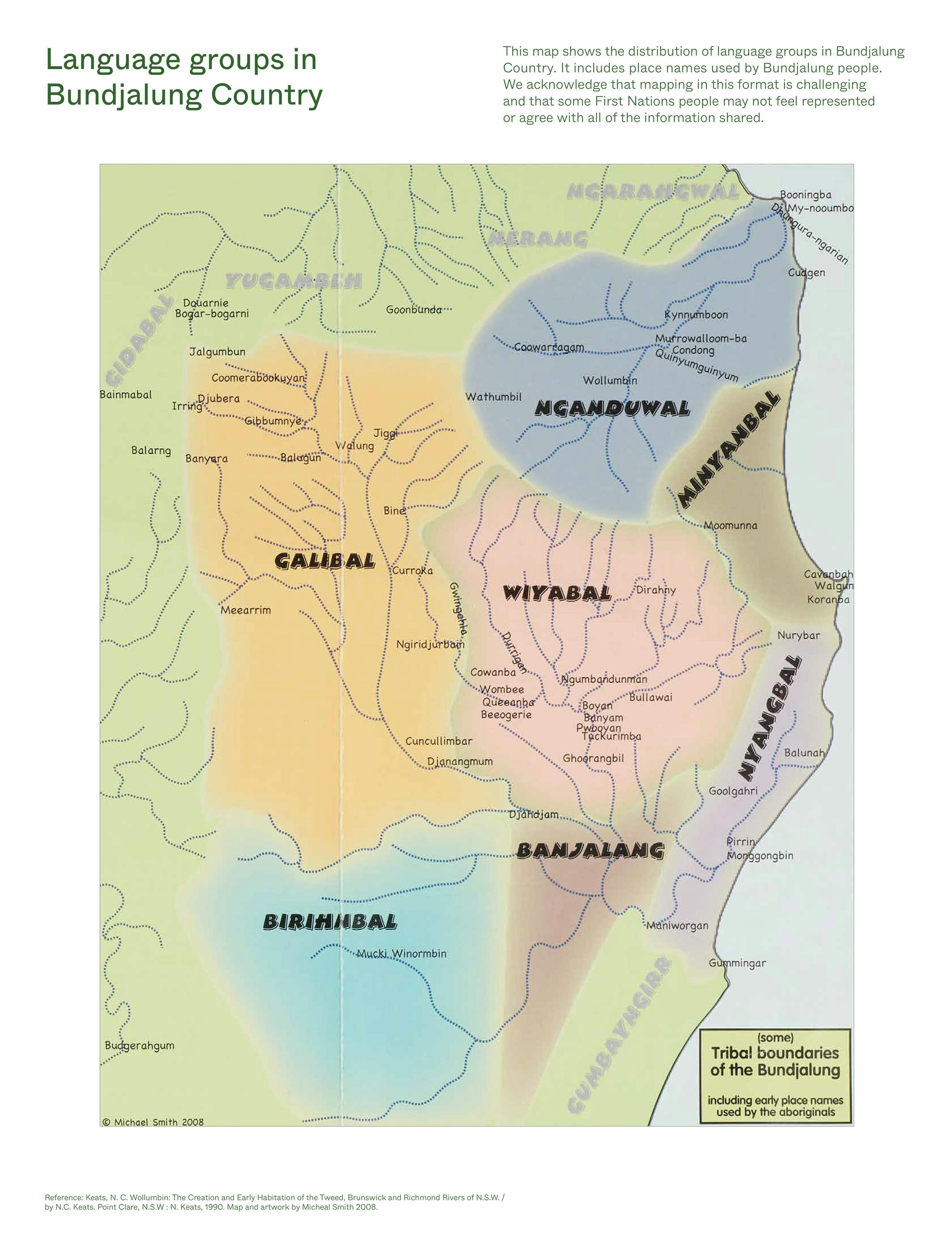

'Tracing the Past, Shaping the Future' explores how Indigenous Knowledge and cultural land management can guide our path toward a more sustainable future. This self-guided exhibition invites visitors to examine the transformation of our physical environment from pre-colonial times to now, contrasting the Bundjalung people's Country-centred worldview with today's Eurocentric human-centred perspective.

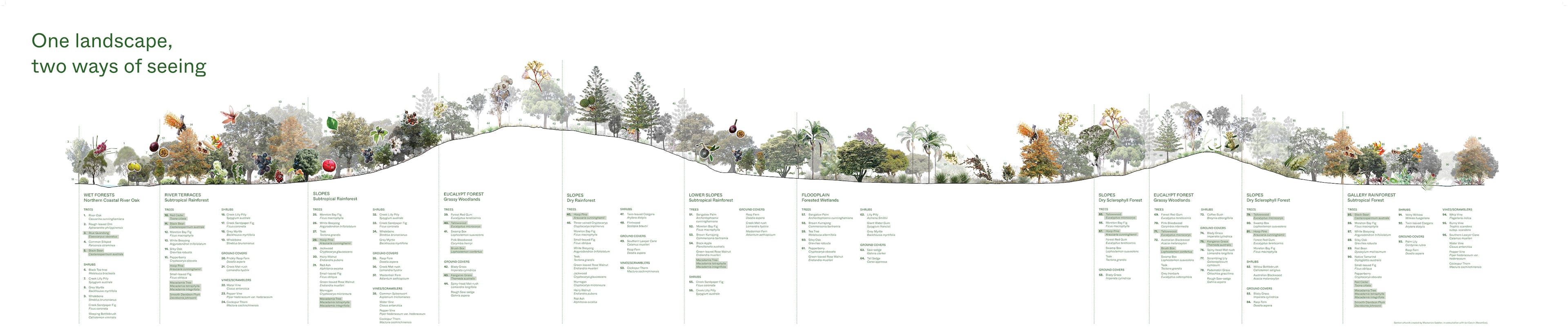

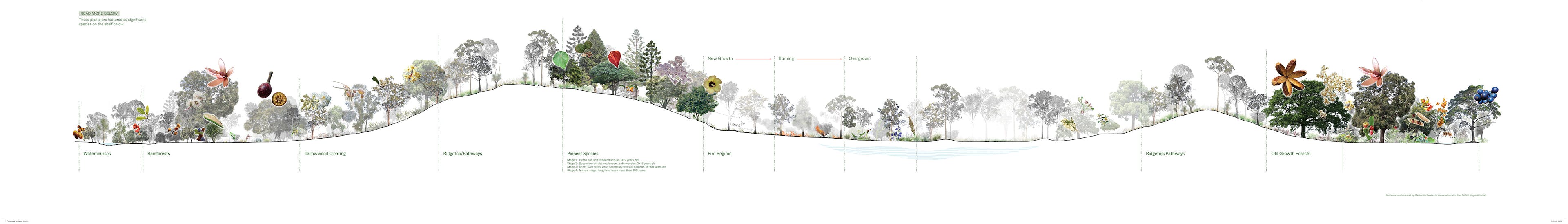

Focused on Widjabul Wia-bal Country, this exhibition brings together maps, landscape sections, plant stories, and case studies that demonstrate the power of Indigenous Knowledge in shaping resilient landscapes. The exhibition highlights different approaches to seeing and managing land, featuring cultural knowledge systems and real-world examples of Indigenous-led practices that help communities adapt to environmental challenges.

The best part? We got the chance to develop this exhibition with our friends at Jagun Alliance, Zion Engagement and Planning, Agency In Design and ReconEco.

Images by Elise Derwin.

Missed the exhibition?

We've created a summary of the exhibition so you can explore how Indigenous Knowledges and cultural land management can shape a more sustainable future.

A magnificent red cedar tree. Photo by Tom Wolff.

Earlier this year, we asked the Lismore community about their vision for our town's future, gathering ideas through meetings, small group chats and many cups of tea. One of the most consistent themes across these discussions was the opportunity to shape our future through Indigenous Knowledges and culture.

This dovetailed with the NSW Government's commitment to ensuring that all built environment projects in the state are developed with a Country-centred approach, guided by Aboriginal people, who know that if we care for Country, Country will care for us.

But what does it really mean to work with Indigenous Knowledges?

What do people mean by cultural land management?

How can—and should—Indigenous custodianship integrate with European concepts of land ownership, planning and management systems?

Human-centred or Country-centred

This diagram is a simple representation of a complex idea, illustrating the fundamental change in thinking that connecting with Country requires. A human-centred approach is illustrated by a hierarchy that prioritises humans over nonhumans and Country, whereas a Country-centred approach is represented as a circular network of integrated relationships.

Source: Diagram adapted from German architect Steffen Lehmann’s ‘Eco v Ego’ diagram, 2010

Cultural knowledge systems

Aboriginal knowledge is developed, experienced and shared through cultural practices of communing with Country, sensing Country, and being on Country. Each of these practices is interlinked, and each informs and deepens cultural knowledge.

Behavioural change

Changing established ways of working is challenging. This diagram shows how our processes of thinking, feeling and behaving are interlinked.

Combining knowledge systems

There are similarities between these systems of cultural practice and behavioural change. This diagram combines cultural practice and behavioural change systems.

All diagrams above feature in the ‘Connecting with Country Framework’; used with permission from Government Architect NSW.

This map shows the distribution of language groups in Bundjalung Country. It includes place names used by Bundjalung people. We acknowledge that mapping in this format is challenging and that some First Nations people may not feel represented or agree with all of the information shared.

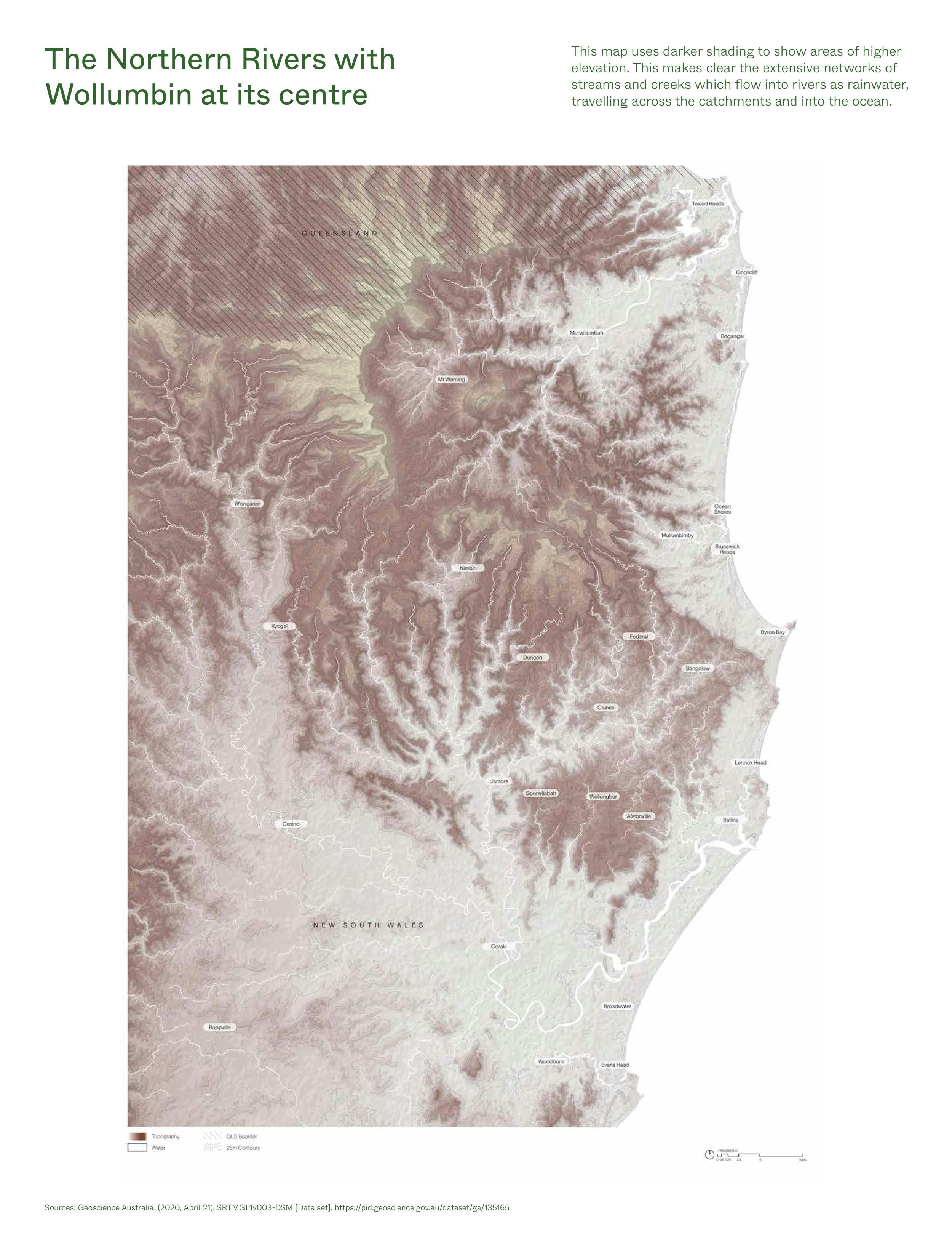

This map uses darker shading to show areas of higher elevation. This makes clear the extensive networks of streams and creeks which flow into rivers as rainwater, travelling across the catchments and into the ocean.

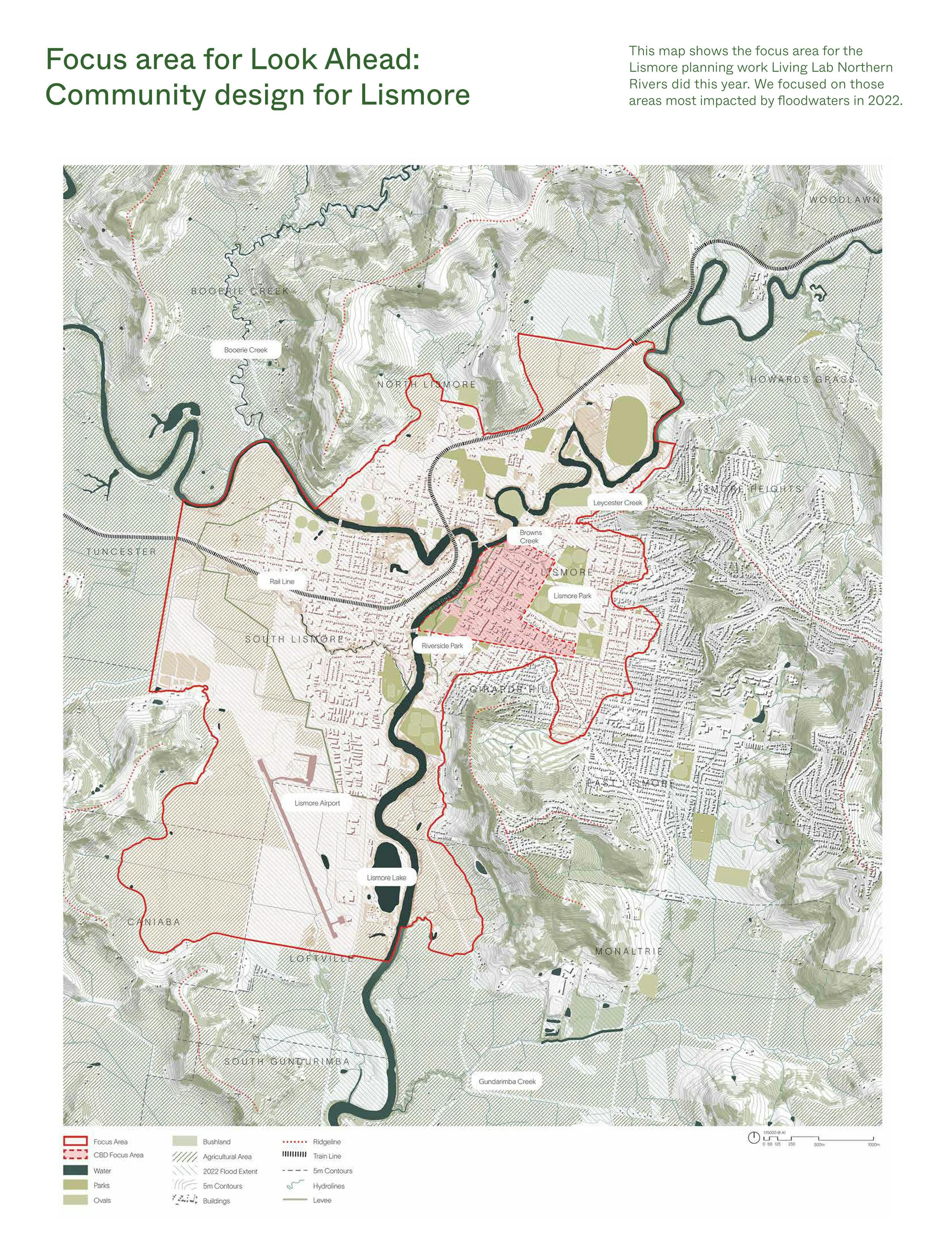

This map shows the focus area for the Lismore planning work Living Lab Northern Rivers did this year. We focused on those areas most impacted by floodwaters in 2022.

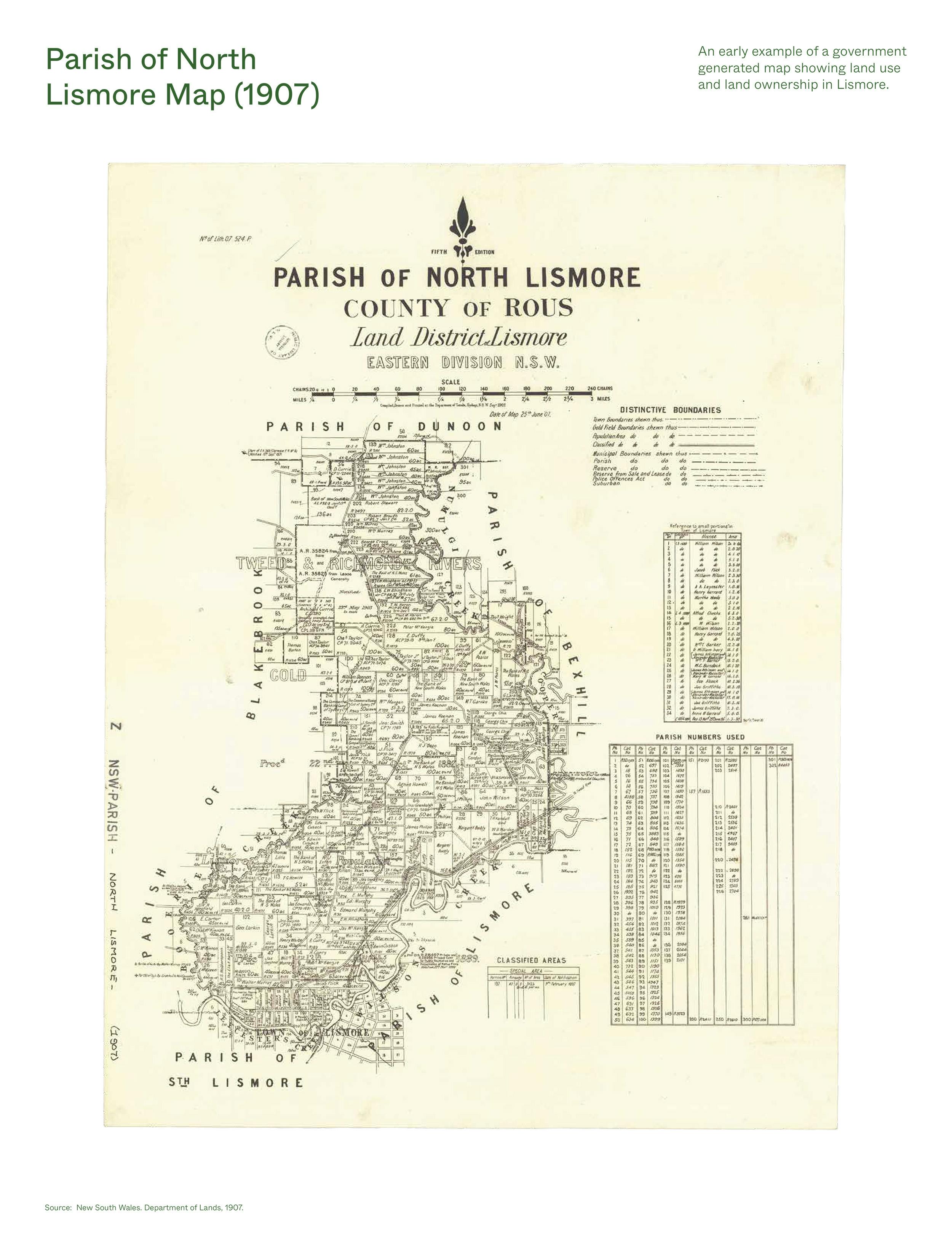

An early example of a government generated map showing land use and land ownership in Lismore.

Maps, like these ones above, come from a particular way of seeing the world — a European perspective.

But there are many different ways that different cultures understand and represent landscapes, and cartography (or map making) is just one of them. It’s important to note that maps have often been used to justify the dispossession of land and erase peoples’ ties to place. This has been especially true in Australia.

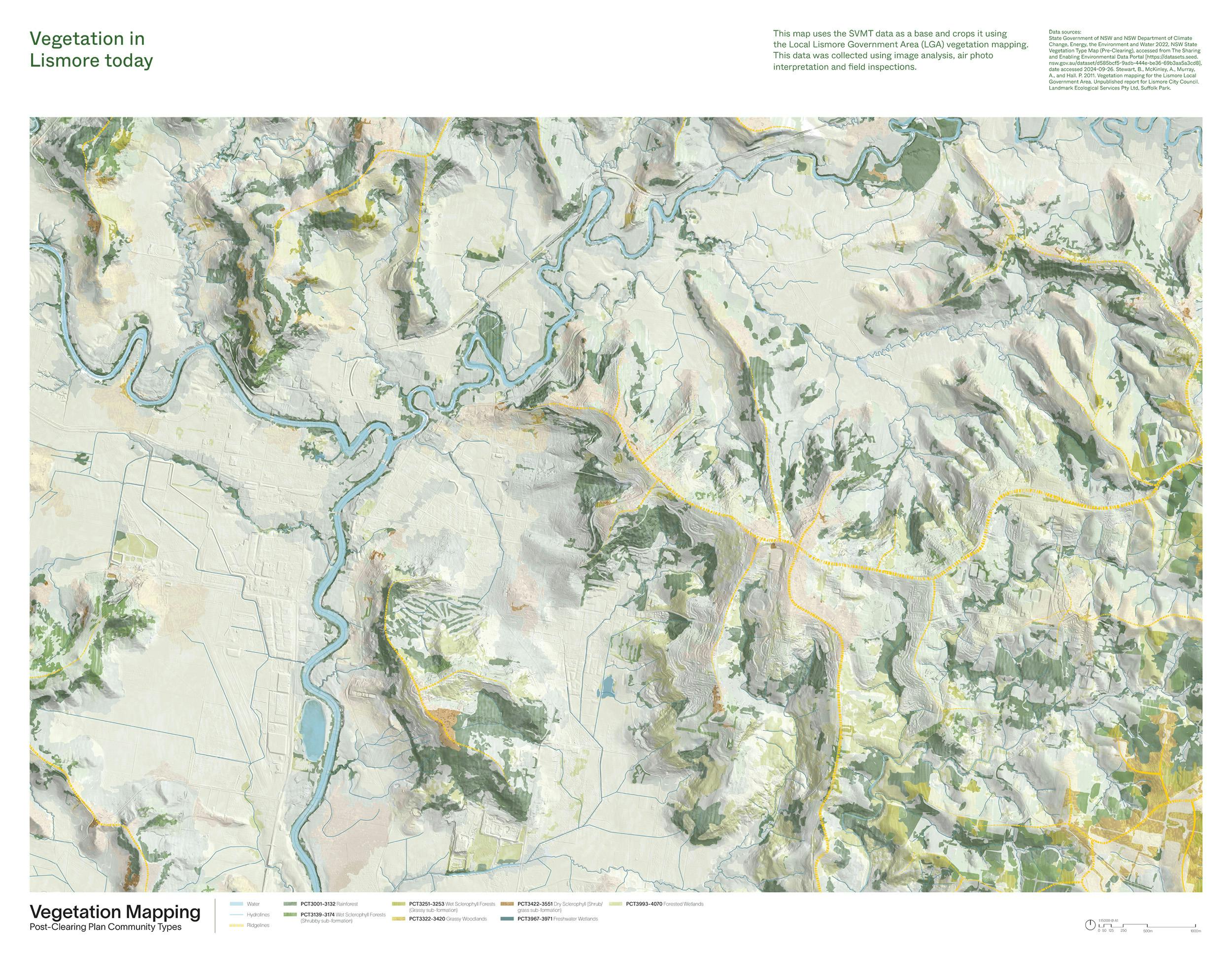

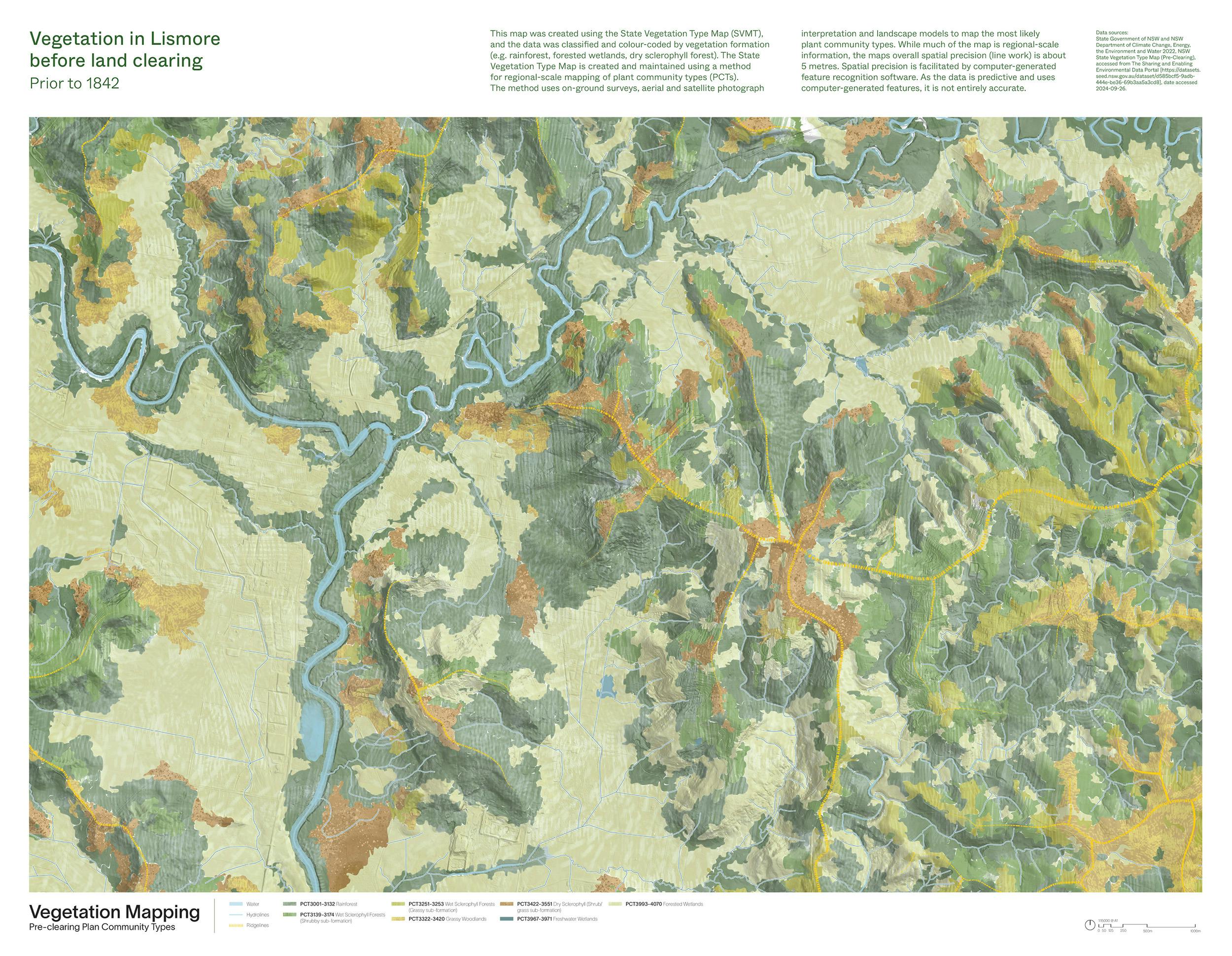

Vegetation mapping

The two maps above show the same area of land at different points in time. They are also designed to show only vegetation communities and they do not show any roads, buildings or other features of this landscape.

The first map shows the vegetation communities that research suggests were present prior to the arrival of European settlers around 1842. The second shows vegetation communities today in the same area.

What map shows a landscape that was culturally managed with a Country-centred approach?

What map shows a landscape changed by a human-centred approach?

Using a method of visual dialogue, a visitor draws and writes her responses to a series of questions, exploring her connection to Country.

Sowing the future

Aboriginal and Western Knowledge systems have a lot in common: both rely on observation, experimentation, recognising patterns, testing ideas and drawing on creativity and intuition.

Each way of knowing offers valuable insights into how we interpret and connect with landscapes.

In this exhibit, we’ve recreated sections of plant life as they might have existed in North Lismore before colonisation. By looking at these diverse plant communities, we invite you to reflect on how we value and connect with this place. It’s a chance to explore different ways of seeing the land, while acknowledging the important cultural differences in how we understand and relate to Country.

An invitation

The different sections in this exhibit invite us to trace the past to help shape the future of North Lismore. By reflecting on history, we can envision a future where Bundjalung Knowledges lead the way in restoring Country.

By looking at the damage caused by past land use practices, we can see how European approaches to land management have often contributed to the extremity of natural disasters, with devastating outcomes for Country and the broader community.

While extreme weather events occurred long before colonisation, First Nations communities had a deep Knowledge of Country’s natural cycles. This understanding helped them build resilience and adapt, moving away from areas likely to be impacted, thanks to the temporary nature of their built environment.

We invite you to imagine a future for North Lismore that prioritises natural systems, centres Indigenous Knowledges, and draws inspiration from the plant communities that can help heal Country.

Elle Davidson, Balanggarra

Director, Zion Engagement and Planning

Aboriginal Planning Lecturer, University of Sydney

Note:

The sections featured as 3m wide panels, and therefore it's very difficult to convey the detail on our website. If you're interested to see the larger file please download the exhibition summary above on this page.